More than six years ago, shortly after starting management at Flying Nun Records, I drove out to the Auckland Warner Music NZ warehouse and distribution centre. It was a massive airport hanger style building, on Rosebank Road, near Avondale. The warehouse was filled with towering industrial style shelves of CDs, DVDs and videos. At the time, it was the central distribution centre for all three major record labels, so there was a lot of stock.

Because Flying Nun had previously been owned by Warner Music, the master tapes were said to be stored in this labyrinth of a warehouse. I wanted to check them out and find a few things for projects we were working on.

The warehouse manager used the forklift to access two large crates of Flying Nun materials that were stored somewhere hard to access, several stories up, near the ceiling. They were probably stored beside overstocks of Jimmy Barnes VHS tapes, or similar.

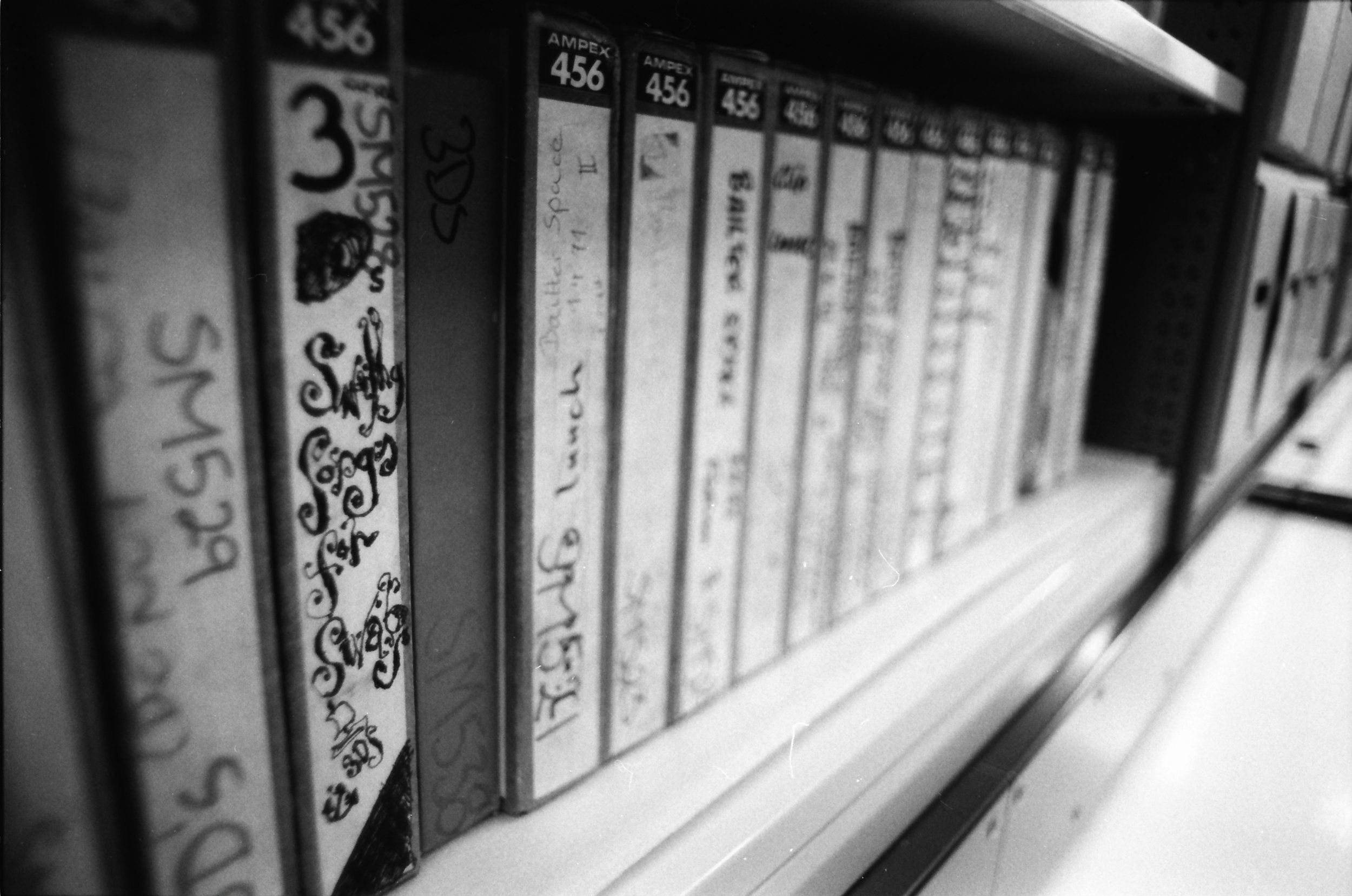

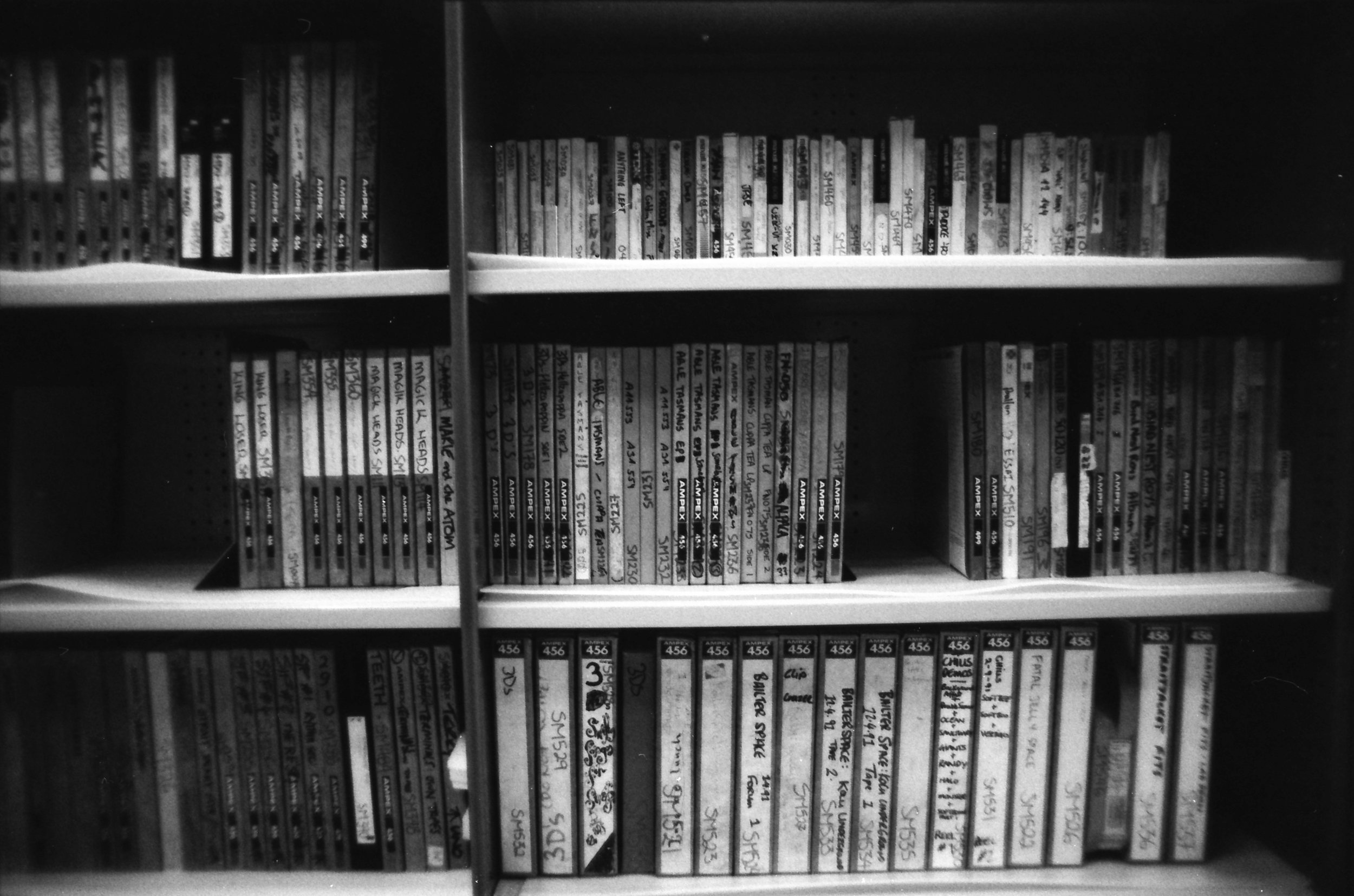

Once the crates had been manoeuvred to solid ground, I dived in to see what I could find. There were a lot of beta tape music video masters, quite a few other strange tape cartridge tape formats (apparently used to create CDs) and piles and piles of folders filled with old yellowing 1980s and 90s computer paper printouts...the style with perforated holes on either side. They looked like they would take a year to read, longer to decipher.

I was told these were the Flying Nun masters tapes. All of them.

The warehouse manager was absolutely sure that was the lot. Flying Nun was “a great Kiwiana label”, he said as an aside (more than once), but this was the entire collection held at the warehouse. After rummaging around under the mountains of computer paper, I asked again. “So where are the actual tapes? Like two inch, one inch and half inch analogue reel to reel tapes?” Not having seen the tape collection before, I wasn't quite sure what I was looking for - but surely there was more than this?

“This is it,” he said.

It wasn’t viable or possible to search this entire giant warehouse. I couldn’t drive a forklift. After checking again, with a bit of a sinking feeling, I left. Where were those tapes, I wondered?

The warehouse manager had told me a year or so earlier label founder Roger Shepherd had loaded up a rental truck to overflowing and departed on the ten-hour drive to Wellington. Perhaps the tapes were in the truck? Roger confirmed he had indeed loaded up a vehicle, but he only took press and newspaper cuttings, posters and other items. No tapes.

Not wishing to alarm anybody, I kept the issue quiet and emailed the manager of Warner Music NZ. He responded to my accusing email by insisting he didn’t throw out any tapes, what was in the warehouse was the same as what he’d received. I asked former Flying Nun, Mushroom Records, Festival and Warners staff. They remembered the tapes but didn’t know where they were. I couldn’t isolate a point where the tapes had disappeared. Because I hadn't seen them it was hard to know what I was looking for.

As time passed, I kept looking for the missing tapes but resigned myself to the fact they might be gone. I’d asked several more times about it and was told what I'd seen was definitely it. In general, I kept this knowledge to myself. I didn’t know what else to do and I hoped they might turn up soon.

A few years later, the Flying Nun distribution contract with Warner Music expired. This deal was part of the Flying Nun purchase back agreement from Warners, and we were keen to move on and establish our own New Zealand distribution. At the same time, the major labels were also shifting warehouses, so I got the call to come and pick up the crates of Flying Nun stuff. I went back out to the Rosebank road warehouse (with a truck) to collect those old beta tapes, yellowed 80s computer printouts, folders and miscellaneous items.

Predictably, when I arrived at the warehouse, there, sitting in some additional crates, were all the missing master tapes. Everything, from the early 80s quarter inch tapes - often featuring the distinctive hand-writing of Chris Knox - through to the two-inch 90s tapes from big studios like York Street. They looked great. I was pleased to see them.

From the Warners warehouse, Matthew Davis (also Flying Nun) and I transported the tapes first to our office in Newmarket, then not long after, lugging them again to our new premises at the Flying Out shop in Newton.

There were boxes and boxes of them. They were very heavy. Neither of those offices had a lift, and both were upstairs. Dylan Pellett, formerly of Flying Nun in the 90s and early 2000s, had helpfully written encouraging notes on the outside of every single box: “This one is heavy!” “This bastard is heavier!” “oi - watch your back!” and so on. He was right, shifting them was not a job for weakling music types.

A later stocktake revealed almost 1,200 individual items, including masters on open-reel magnetic tape, multitrack, demos, and live recordings, dating from 1981 until the mid-2000s.

The tapes were then stored in a large walk in cupboard in the corner of my office. They took up a lot of space.

At that time, the Flying Out Record shop had just opened downstairs in our new premises. We had many regular customers, among them was Brent Giblin. I had met him some time ago and knew he had somehow been involved in restoring some old 8mm film footage. One day the tapes came up in conversation, and he mentioned he had some experience in tape preservation and cataloguing. Clearly, he knew more about it than any of us. As a generally helpful person and a fan of Flying Nun, he offered to take a look at the tapes. Somehow, that turned into him volunteering to catalogue, inspect and check every single tape that was stored in my office cupboard. It was a time-consuming project that in the end took him more than a year.

After closer inspection, Brent confirmed the tapes were in good condition. But due to their age, he thought some would start to degrade. Possibly soon. While our cupboard was OK, they really needed to be stored in a climate controlled environment. We also needed to think about digitising them properly to preserve them for the future. Many tapes had been digitised before, but none of the individual tracks on the multi-track tapes. Also, analog to digital technology had come a long way since any previous digitisation in the 1990s.

Around this time, a group of supporters of the label were starting to discuss an idea around the preservation and archiving of Flying Nun materials - broadly including music, posters, photos and historical documents. Initiated and led by Sneaky Feelings band member David Pine, the group had some informal meetings with interested parties in New Zealand’s main centres. The group also involved Flying Nun founder Roger Shepherd, as well as artists like Denise Roughan (3ds/Ghost Club/Look Blue Go Purple) and Francisca Griffin (Look Blue Go Purple) and other people with a long-running connection with the label like Barbara Ward, Russell Brown, Caroline Stone, Stephen Steadman and Ian Dalziel.

Among the discussions of this new group was the question of what to do about the tapes. A rough calculation of the costs for professional digitisation would require around half a million dollars. There were many tape formats so you would need lots of different rare and old tape machines to do it, and people with a high level of specialised skill. It would take a lot of time.

The Flying Nun label was not in the financial position to shoulder this cost. The record label business in 2018 - and the music business in general - does not have significant amounts of surplus cash. Additionally, while digitising and preserving the tapes would require significant expenditure, it would generate minimal income or financial return. It was not a sound business investment.

So Flying Nun and the new group (which was now called The Flying Nun Foundation) began exploring other options. One possibility that seemed promising was the National Library of New Zealand, the Alexander Turnbull Library. After several meetings with Music Curator Michael Brown, we decided to take a trip to Wellington to take a look around their premises.

We were all impressed by the Library’s vast underground temperature controlled labyrinth, the multitude of old tape machines and most importantly the commitment and attitude of people that worked there.

But, we still had some concerns. One was that Flying Nun and many of the artists are still recording and releasing music; if we hand over the tapes, what happens to the copyright? Traditionally the “master tape” is considered the source of both all subsequent recordings and also the original copyright. While the artists and label are still active, we can’t just give that away.

Additionally, if the library makes digital copies of all the tapes, do they have the time and money to invest in this massive job? Will it actually get done? If it does, then who has rights to those digital copies? Who will they be available to? Finally, and most importantly, would the artists support this project?

These were among the questions in our mind when Roger and myself, in consultation with the Flying Nun Foundation, started discussions with the Alexander Turnbull Library. They understood that we couldn’t just hand over all ownership of the recordings and we also needed a clear (and timely) programme of digitisation. They also realised it was important to consult with the artists about all of this. Fortunately, although it took more than two years to thrash out the details, the negotiation was not a difficult process. We all had a shared goal of preserving and protecting the music - it was just about finding a way to make that work for everyone.

In the end, we collectively came up with a strategy. Subject to the artist's agreement, Flying Nun would donate the tapes to the Alexander Turnbull, and the library would agree to digitise the entire catalogue within three years - an ambitious, expensive but not impossible target. The copyrights and intellectual property ownership of the master recordings would remain as they were before (with the artist and label), but the physical tapes would become part of the library collection.

After a successful period of consultation, where Roger travelled the country outlining this proposal to all the artists and stakeholders, an agreement was finally signed with the Alexander Turnbull Library. Shortly after, the project was announced by Internal Affairs Minister Tracey Martin and Associate Minister of Arts and Culture Grant Robertson.

The press release included the following text:

Flying Nun Records, the iconic New Zealand music label, is donating many hundreds of master tapes from recordings made between 1981 to the mid-2000s, to the Turnbull Library’s Archive of New Zealand Music. The collection includes tracks from legendary New Zealand artists such as The Chills, The Bats, The Verlaines, Jean-Paul Sartre Experience, Look Blue Go Purple, Sneaky Feelings, Headless Chickens, and Bailter Space, amongst others. The donation is a major event that marks the beginning of the Library’s centenary period, 100 years since the original donation by Alexander Turnbull himself.

It was thirty-seven years since the Flying Nun tape collection was started in 1981. Many people had previously gone to a lot of trouble to take good care of it (including Warner Music, even if I thought they had lost them). Now the collection could be properly preserved for future generations to appreciate and learn about. The tapes had found a final home.