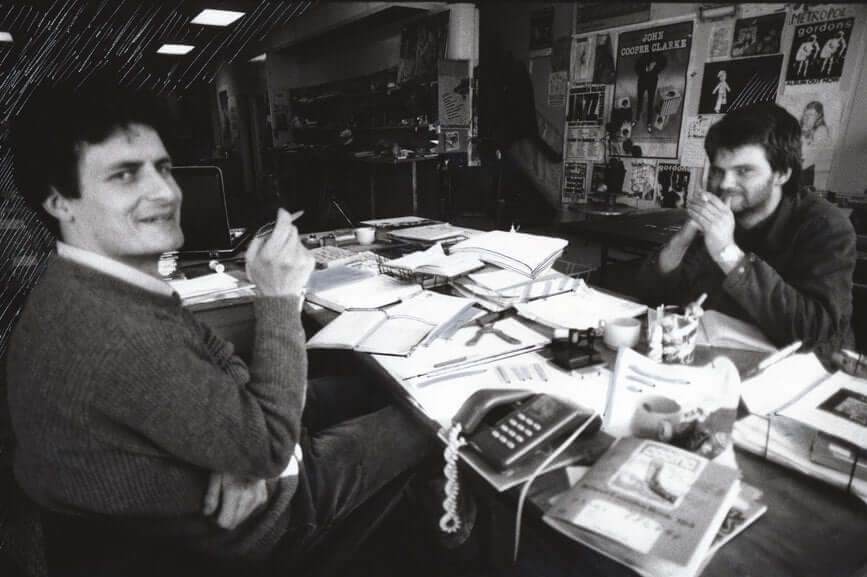

Hamish Kilgour and Roger Shepherd, Flying Nun offices, mid 80s. Credit: Photo by Stuart Page

I first met Hamish Kilgour in 1981 on the stage at the Gladstone Tavern in Christchurch. His band, The Clean, had just played an astonishing set. I knew they were probably the best band I would ever see, and I had to get up close as soon as they finished and get talking. I found Hamish to be unaffected, modest and engaging. This was just the start of it all.

Hamish was born in Christchurch and grew up in the small South Island rural towns of Cheviot and Ranfurly before he landed in Dunedin in the early 1970s. I can't imagine that Otago Boys High School suited his free-spirited nature. There was a stab at university and a time as a journalist, but those lives weren't really his. He was locked onto the longtail end of the counterculture, and many of the interests and traits that it encompassed (equal rights, free-wheeling, authentic and meaningful music, freedom of expression, distrust of the “man”, etc.) stayed with him throughout his life.

No hippie, he hung out with his Dunedin friends Chris Knox and Doug Hood and, like them, was energised by the arrival of punk, a wave of cultural change driven at the start by raw, uncompromising music that encouraged action and change opposed to the status quo of passivity and stagnation. Hamish kept on board the worthy concerns of the counterculture but embraced the new ethos in terms of music and worldview. He promptly found a drum kit and formed a band with his brother David.

The Clean assembled a few weeks after the Enemy, but whereas the Enemy were born as almost the complete package of quality songs and performance, The Clean struggled to construct simple songs and seemed unable to master their instruments. They were a work in progress, and it would be a couple of years, a succession of bass players, a programme of writing and demoing a collection of songs and a hardening of their resolve before they were truly ready to take on the world.

Hamish, David and bass player Robert Scott did make a decent go of it all with considerable commercial and critical success in New Zealand over 18 months or so in 1981 and 1982. The band had a crazy time with a string of incredibly successful records (Tally Ho!, Boodle, Great Sounds Great and ‘Getting Older’). They showed that records could be made differently, that those records could sound great and that they could sell in big numbers. That New Zealand music was just as valid as something from London or New York. That it didn't have to be validated by commercial radio in order to be worthwhile. There was a shift in consumer attitudes towards New Zealand music, and The Clean epitomised that change; Hamish was the articulate advocate who most effectively pushed the cause.

All of the members of The Clean wrote songs. This was a major part of their appeal. The quality and variety of the songs. Hamish’s tended towards the sharper edge of agitprop (he liked that word), ones that spoke to issues in a pointed and direct manner. He was a fine musician who was not defined by his instrument, the drums. In the beginning, he was the “motorik” drummer who drove The Cleans' thrilling “Point That Thing Somewhere Else." Much later, he was the guy with the sack of percussion instruments over his shoulder who would spontaneously break out his maracas and join in with any band and in any situation. He also played the guitar. When I last saw Hamish perform, it was at the Paekakariki Hall in the late 2010s. He played a set of free-sounding jazz-styled guitar. Studied and refined over many years or made up on the night, I am not sure. Whatever it was, I felt tempted to run over and offer him a recording deal.

After The Clean disbanded in 1982, Hamish wrote an application to get a work scheme supported job with Flying Nun. I was the last to know about it; he must have forged my signature, but it was exactly the right thing to do; I desperately needed the help. He performed the traditional tasks of glueing 7” covers, sleeving records (not always accurately), designing newsletters, talking to people on the telephone and packing and dispatching orders. He was serious about his future and that of the company and, off his own bat, did a basic accounting course at night school. Hamish was responsible for organising the first piece of formalised accounting at Flying Nun; the monthly debtor's list and the terrifying creditors' list.

The stress possibly drove him away towards a more sensible job. There was certainly stress once we knew what those incoming invoices added up to, but there was also tension. He believed in music for art's sake rather than something that could be transacted for money. He was uneasy about the sales we chased so we could generate enough income in order to pay the invoices on that creditor's list. I also had a sense that he wanted a career that we couldn't offer, one that would support a settled, more conventional home life. He was going to give that a shot.

After The Clean disbanded in 1982, they could decompress and make sense of what had happened over the previous 18 months. With the pressure removed, The Clean started to release records in a casual occasional way. The Great Unwashed Clean Out of Our Heads (the Kilgour brothers only) album and the Oddities cassettes largely showcase their pre-success Revox 600 recordings, the demos of the songs they were writing that would largely sustain their active period. The Great Unwashed Singles was the Kilgour brothers with original Clean bass player Peter Gutteridge (The Chills, Snapper), and it felt like a kind of stab at a full-blown return, but Gutteridge quickly stepped back, and it was soon over. Flying Nun kept The Clean titles in stock which became increasingly important as overseas sales started to grow. The thinking was that new customers would want to hear the music that inspired the bands that they were now buying. I’d like to think that this laid the foundations for the future not-inconsiderable international interest in the band.

In 1988, The Clean reconvened to play some London dates. Emboldened by the response, they returned in 1990 to record an album, Vehicle. The pattern was set for the next 20-odd years, short fun tours when the terms were good, and they felt in the mood. Albums to record when they felt the creative motivation was right and ready to get a good job done. Modern Rock (1994), Unknown Country (1996) and Getaway (2001) are all delightful pleasures, with each having its own foibles and flavours. The approach worked well. It was occasional, there was no career pressure and ‘the Man' didn't impinge on their lives too much. The last, the 2009 Mr Pop, is a swirly masterpiece.

Back to 1987, on a parallel non-Clean course, Hamish teamed up with Alister Parker (The Gordons) to form Nelsh Bailter Space with Ross Humphries (Pin Group, Scorched Earth Policy and The Terminals) and Glenda Bills. They released a self-titled EP (1987) that includes his song I'm In Love With These Times, which is surely a career highlight. Nelsh Bailter Space morphed into Bailter Space when the band became a trio, with Humphries and Bills leaving and John Halvorsen (The Gordons) joining. This lineup recorded Tanker as Bailter Space in 1988. At the end of a late 1980s promotional trip to New York with the band, Hamish decided to stay; a stay that would last almost 30 years. For much of that time, he was with partner Lisa Siegel. The Mad Scene was their band, and together, they had a son. Hamish enjoyed New York with its abundance of street life and teaming art and music world. He became embedded in the city's music community and made lots of friends from all backgrounds and occupations. His art became florid and fantastical. There is a fine 2015 release he made with Tiny Ruins called Hurtling Through. His final 2018 release, Finklestein, is a remarkable piece of musical eccentricity.

When he returned to New Zealand, he chose to live in Christchurch, the city he always had a stated preference for. He liked the big sky that sits above the flat plain. The ‘void,’ as he once named it on a drawing he gave me. The last year has not been happy or easy. Hamish is, as you will know, in that place: the void that is death.

Hamish will be sorely missed by family and close friends, as well as all in the larger Flying Nun community. He holds a special place within that community as a member of The Clean and as a representative of all that spirals around them, and in his own right as an artist, musician and free thinker. He was a mixture of the 1960s and a post-punk kind full of possibility. He had strong anti-establishment sentiments and non-status quo views, sentiments and views that were usually spot on. He was smart and friendly, with a keen sense of humour and alert to the absurd. Hamish was hard to categorise or pigeonhole; those are places to put the dull and uniform. I will fondly remember him as a kind of New Zealand beatnik, a confident and colourful personality whose life revolved around music and art. He does not feel diminished by death but made larger, stronger and more significant. I can see him striding across that plain wearing his battered hat with his swag of assorted percussion over his shoulder. Confidently walking towards and looking up and into that void.

Farewell, old friend. I’ll see you up there in the wind sometime.

Thanks for this piece, Roger. Sums up Hamish K’s life perfectly. RIP Hamish Kilgour – one of NZ’s rock’n’roll troubadours.

Hi Roger, just to say that it’s hard to imagine a more beautifully written eulogy. Warmest regards.

Excellent farewell, Roger. In fairness (for it must be said) Hamish came to see Flying Nun as “the Man”; among many buttons the unsuspecting acquaintance inadvertently could push. His knowledge of rock music and what had merit was enormous and a fan’s passion. He loved his son dearly. “Thumbs off” is perhaps now too overwhelming to play. Condolences.

There was a college radio station that I, being the proto-hipster of the day, used to listen to in hopes of hearing obscure artists that I could use to blank out the vast wasteland of 80’s hair metal and corporate new wave schlock. The station that introduced me to “Everything’s Gone Green” and “Prole Art Threat” then offered up “Tally Ho!” I was a kid with a crappy guitar and not much potential for impressive shredding, but I loved the way a good song could make me feel. My unarticulated complaint with American Top 40 was that there was a sheen of exclusivity: Rock stars were different than me, apart from me. They were to be adored and I should highly value any exchange at any price. I knew it didn’t have to be that way.

“Tally Ho!” sounded like guys that I could be friends with- It sounded like an inclusive, slightly silly, good time. The musical equivalent of a Treefort Clubhouse. That’s what I was looking for.

I went to college, became a DJ, and formed a band, too. I had been shown and gently prodded toward a great place. Thanks, Hamish. So much of my world orbits around your choices and efforts. Those efforts echo in the ears of all those who found you for long, long time.

Point that thing …… One of my favourite songs ever. See you on the other side brother